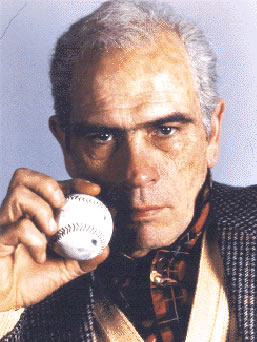

Cobb

Ty Cobb was by many accounts a mean-tempered, vicious, drunken, wife-

beating, racist SOB who was impossible to spend any length of time with,

and the movie "Cobb" faithfully represents those qualities, especially

the last one. Being locked up with this movie for 123 minutes is like

taking a three-day bus trip sitting next to Hunter S. Thompson.

That is not to say the movie is without redeeming qualities. That is not to say the movie is without redeeming qualities.

On the contrary, this is one of the most original sports biopics I've

seen, if only because it tells the truth, or tries to - and because it

contains one of Tommy Lee Jones' best performances. It's the kind of

film where you admire the craftsmanship and artistry while questioning

the wisdom of the project itself.

Ty Cobb was "the greatest baseball player of all time." a fact repeated

many times in the movie. He was the first member of the Baseball Hall of

Fame, the holder of a lifetime batting average of .367 that has still

never been approached, and the inventor of the modern game of baseball.

And he made a fortune in the stock market.

He was also the kind of guy that the other Hall of Famers locked out of

their hotel rooms after the annual ceremony. A base-runner who sharpened

the spikes on his shoes, and sent 12 men to the hospital in one season.

Who went into the stands to punch out a heckler who, it turned out, had

no hands. Who pistol-whipped a man to death. Who was divorced for

wife-beating, whose daughter would not speak to him, who grabbed a mike

in Reno to snarl about "niggers, Jews and dagos," and who kept himself

alive with alarming mixtures of morphine, lithium, insulin and bourbon.

Cobb remains a towering American figure because no one else ever did on

a baseball diamond what he did. He lived until 1961, which means he died

at a time when celebrities were still routinely sheltered from scandal.

If nobody could stand him, nobody made it a point to say so.

Now comes "Cobb," written and directed by Ron Shelton, a former baseball

player whose filmmaking credits include two of the best movies about

sports ever made, "Bull Durham" and "White Men Can't Jump." Shelton

approaches the problem of Cobb from an oblique angle, through the eyes

of a sports writer named Al Stump (Robert Wuhl). Hired by Cobb to

ghostwrite his autobiography, Stump hangs on for a wild, drunken ride

down snowy roads and through Nevada casinos, from the Hall of Fame

dinner to grungy roadside motels and a final rendezvous with death.

Al Stump really exists, and really did ghost Cobb's autobiography,

shaping it into a standard rags-to-riches saga. He has also written a

recent book telling the "real story." In the closing moments of "Cobb,"

his character, who has written two books - one true, one laundered -

decides to publish the lies. "I didn't lie so the children could have a

hero," he tells us. "I lied for myself. I needed him to be a hero."

Scribbling notes in the dark, I wrote down "hogwash!" The movie never

ever shows us why Stump needed Cobb to be a hero.

Its problem, indeed, is that it doesn't know what to do with Stump in

the first place. Cobb is a magnificently evil and deranged character,

ranting and raving, shooting bullet holes through walls and ceilings,

making a public nuisance of himself, crashing automobiles, disrupting

meetings, and participating in an ugly sexual assault at gunpoint. He

has been deeply damaged, and we find out why as the story gradually

emerges about the death of his father - who was killed by Cobb's mother,

or maybe by her lover, or just perhaps (I would hazard) by Cobb himself.

Cobb wants Stump to put only the good stuff in his book, and so he

conceals many of the seamy details. To work them into the movie Shelton

hits on the clever idea of a newsreel about Cobb's life. We see it at

the beginning of the film, and then it's played again at a Hall of Fame

dinner in his honor - only this time, the drunken Cobb hallucinates that

the newsreel is showing what really happened, and so we see the murder,

the scandals, the domestic violence, the misery.

Cobb is there, in the round, and convincing. Oliver Cromwell once urged

a painter to make an honest portrait, "warts and everything," and "Cobb"

makes its hero look like all warts, with a batting average attached.

Cobb is fine. The movie's weakness is that it gives Stump no place to

go, no way to develop.

Awestruck by Cobb's greatness, he puts up with drunken rages and violent

escapades like a battered wife. As their odyssey takes them from state

to state, they fall into almost a domestic arrangement: Stump as

biographer, chauffeur, stenographer and nurse, "the only thing keeping

the bastard alive," occasionally making shrill threats to leave, but

never following through on them. Does he learn anything? Served with

divorce papers, he pulls a gun on the process server and puts some

bullets through the walls, emulating his hero.

Shelton works hard to inspire even marginal sympathy for Cobb, and it is

to Tommy Lee Jones' credit that some does develop, for example during a

maudlin visit to the crypt Cobb has built for his reunion after death

with a family that cannot stand him alive.

Cobb is a lonely, unpleasant alcoholic, and Stump, by the end of the

movie, is just as lonely and alcoholic, but does not have it within

himself to be unpleasant on such a heroic scale.

I've seen the movie twice. The first time, I found Cobb so unpleasant

and Stump such a toady that I couldn't understand why anyone would want

to make a movie about them. The second time I was able to focus more

clearly on the strength of Jones' performance. I suppose if I rode a

Greyhound long enough sitting next to Hunter Thompson, I might get to

appreciate his fine points, too, if he didn't shoot me first.

|